St. Simons African American Heritage Coalition is a nonprofit organization with a mission to educate people about African American history here on Georgia’s largest barrier island; to preserve the remaining ancestral lands and homes; and to revitalize our Gullah Geechee heritage through tours, programs, and festivals throughout the seasons.

As St. Simons Island became increasingly popular to visitors and people seeking to live here in the mid-20th Century, three African American neighborhoods on the island were imperiled. Then and now, we experience development encroachment and the erasure of our quality of community for new subdivisions, and cemeteries ringed by golf courses and modern retreats.

SSAAHC is comprised of African American property owners and concerned citizens who care about preserving the heritage of the original African American communities on this island.

Since its formation in 2000 at the First African Baptist Church of St. Simons Island, the St. Simons African American Heritage Coalition rejoices in community gatherings and tours of our historic schoolhouse as a treasured community center and meeting place for Gullah Geechee celebrations.

Events Calendar

-

Feburary

Tea & Ties That Bind

Feb 1st, 2026 3pm - Read More

-

March

Revolution on the Coast 250 Celebration

March 12,2026 6PM- 7:15PMRead More

-

June

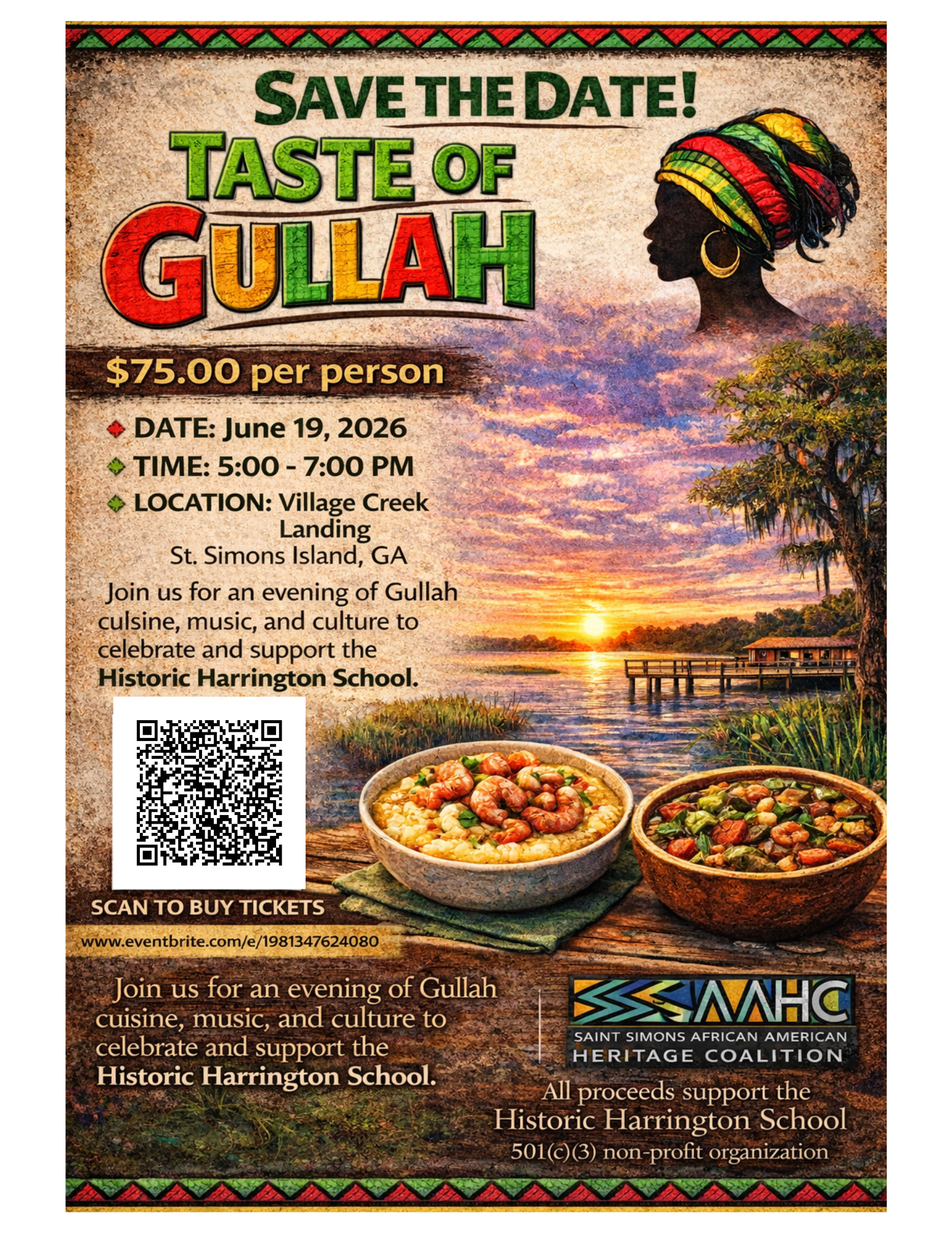

Taste of Gullah

The Annual Taste of Gullah is back and better than ever! Join us for an unforgettable evening celebrating the flavors, culture, and living legacy of Gullah Geechee heritage, hosted by the St. Simons African American Heritage Coalition. - Read More

-

July

Civil Rights

Segregation, Voting Rights, NAACP, Black Wall Street

-

August

Preserving African

American HeritageBuildings, Family History, Cemeteries, Organizations, Success, Challenges

-

September

Education

Schools, Teachers, Lessons Taught at Home

-

Feburary

Tea & Ties That Bind

Feb 1st, 2026 3pm - Read More

-

March

Revolution on the Coast 250 Celebration

March 12,2026 6PM- 7:15PMRead More

-

June

Taste of Gullah

The Annual Taste of Gullah is back and better than ever! Join us for an unforgettable evening celebrating the flavors, culture, and living legacy of Gullah Geechee heritage, hosted by the St. Simons African American Heritage Coalition. - Read More

-

July

Civil Rights

Segregation, Voting Rights, NAACP, Black Wall Street

-

August

Preserving African

American HeritageBuildings, Family History, Cemeteries, Organizations, Success, Challenges

-

September

Education

Schools, Teachers, Lessons Taught at Home

Join us in our journey to revitalize

St. Simons Island’s African American heritage.